Now women return from afar, from always: from "without," from the heath where witches are kept alive; from below, from beyond "culture"; from their childhood which men have been trying desperately to make them forget, condemning it to "eternal rest."1

— Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa

In January 2016, Julie Hill and Catherine Anyango Grünewald opened the Edwardian Cloakroom in Bristol for hysteria and sorcery. Ladies’ Room was the second in a series of collaborative exhibitions, Crying Out Loud, between the two artists considering fictional representations of femininity and the cultural and historical realities of women’s social and sexual autonomy. The ladies’ room, by its very notion, is a space occupied exclusively by women. Whilst this space may signify one of the two binaries excluding the infinite variations within the sex/gender spectrum, or connote the internalised disciplining gaze which continues to mark woman as the other of man and as the object of scopophilia par excellence — it is, after all, the space where women retreat to powder their noses — it also retains a subversive potential. Hill and Anyango’s take on the ladies’ room demonstrates how an exclusively women’s space may allow for social and political agency free from phallocentric authority and give rise to powerful instances of bonding, solidarity and camaraderie amongst women. In such a setting, stereotypically feminine tropes can be transformed into powerful tools for claiming agency. This potentiality is epitomised by two antiestablishment feminine figures who were also present in Ladies’ Room: the hysteric and the witch.

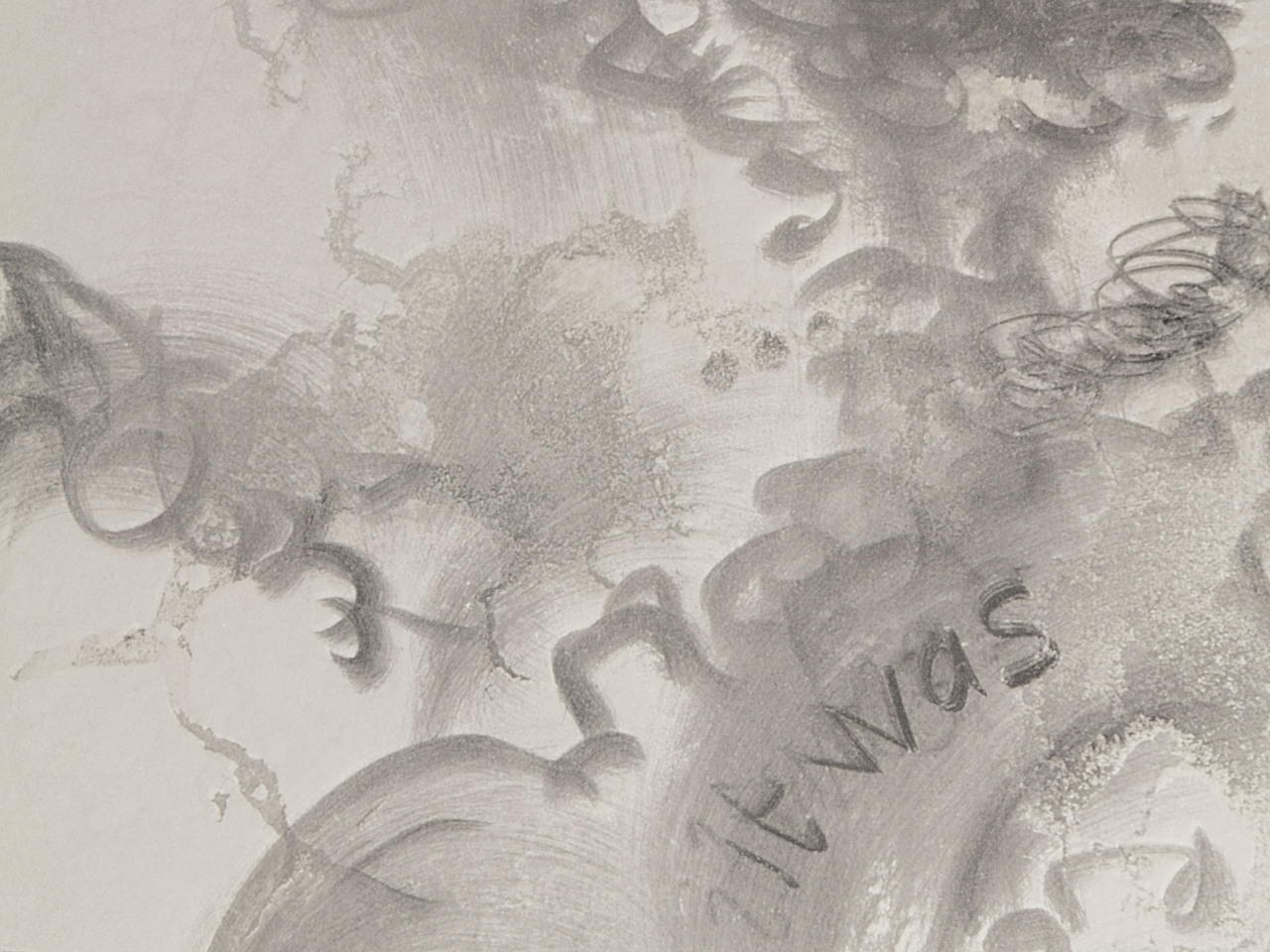

The exhibition featured two installations, Hill’s It was… and Anyango’s Silent Companion alongside Anyango’s painting series Sanctuaries. It was… derives from Hill’s research into the history of cinematic horror portraying women’s sensitivity to otherworldly resonances and alluding to the instability of the feminine psyche. Silent Companion addresses the history of women’s alternative medicine practices that have subverted anti-abortion laws in the Edwardian era, whereas Sanctuaries makes visible women’s devalued maintenance labour within the domestic sphere.

Hill’s combination of installation and performance filled the Edwardian Cloakroom with smoke, misty mirrors and cryptic messages borrowed from canonical horror films ranging from Suspiria to Poltergeist to Cat People. These messages, carved onto the mirrors and floating through space as gentle whispers, alert their recipients to looming dangers and hint at the anonymous messenger’s magical abilities. Reminiscent of spells, like verbal eruptions of the hysteric’s unconscious at work, the utterances reach beyond the rational and familiar world, calling for the unknown and unpredictable other to surface from within: ‘Reach back into our pasts, when you had an open mind’; ‘I saw the secret behind the door, the iris’, turn the blue one…’

It was… demonstrates how, in the phallocentric symbolic, the imagined bond between femininity and the supernatural marks women as deranged hysterics and powerful witches who, uncontrolled, pose a serious threat to the societal order driven by masculinity. It is men who operate as agents of God reaching for pious spirituality, and as masters of reason, civilisation and culture. In contrast, women’s disruptive power belongs to the menacing nocturnal realm bound to volatile forces of nature — the occult stemming from beneath the earth and connected to the devil. This is why women have for centuries been socially and sexually subdued; to stop them from unleashing their potentially deadly powers as dangerous practitioners of witchcraft.2

The fear of unruly femininity and female sexuality unleashed is outrageously evident in one of Hill’s key references, Dario Argento’s Suspiria from 1977. The film is set in a remote women’s dance academy in the depths of a wild forest in Freiburg. The academy is run by malevolent witches who practice black magic and murder innocent, young women who fit the societal standards of submissiveness, passivity and beauty deemed proper to the female sex in the masculine biblico-capitalist society. Jacqueline Reich argues that, directed during the peak of second wave feminism, Suspiria is a cinematic articulation of masculine anxiety in the face of women’s sexual emancipation.3 It also parallels sorcery and mere belief in magic with hysteria as a form of mental illness.4 Whilst Argento’s film ends triumphantly with the academy bursting into flames and balance being restored as the murdered witches’ corpses burn in their destroyed lair, It was… challenges this conventionally structured narrative. Hill allows the presence of the hysteric and the witch to linger without forceful restraint or a climactic moment of destruction.

Where Witches Are Kept Alive

Julie Hill, It was… (2016), talcum powder/cosmetics on mirror

Catherine Anyango, Silent Companion (2016), watercolour and enamel on ceramic tiles

Where Hill unfolds fictional representations of rebellious femininity, Anyango’s Silent Companion obliquely touches on the historical legacy of witchcraft through alternative medicine and natural healing. Silent Companion is a series of bathroom tiles with painted botanical illustrations of abortifacient herbs, which provided solace to many women in the occurrence of unwanted pregnancies when abortions were still illegal. Although the architectural context of the exhibition connects herbal abortions with the Edwardian era — the height of the suffragettes movement and a key historical moment of women’s revolt — the history of abortions performed by women can be traced back to pre-feudal and feudal societies that preceded three centuries of witch hunts from the 1400s till the 1700s.5

Silvia Federici writes that practicing magic as a healer, midwife, herbalist or maker of love potions was a source of employment and power for many women in pre-capitalist societies. Untamed female sexuality, which has historically been associated with disorder and disruption of discipline, has always been seen as the core of women’s magic.6 When the foundation of capitalism was laid out during the land enclosures and the introduction of exploitative wage labour, women’s sorcery – which entailed methods of abortion and contraception — became a serious threat to inducing the new social and economic hierarchies and had to be eradicated. Federici argues that the barbaric witch hunts resulted in a new model of femininity better suited to the development of masculine capitalist societies and gendered division of labour: ‘sexless, obedient, submissive, resigned to subordination to the male world, accepting as natural their confinement to a sphere of reproductive activities’.7 The legal prohibition of birth control and abortion under such conditions was an attempt to ensure the steady reproduction of new labour force8 and to bind women to the domestic sphere of unpaid labour as compliant wives and mothers. Silent Companion meditatively reveals the subversive legacies of witchcraft that could protect women from the confines of motherhood and housework, and the consequent economic dependency on men. The dummy boards accompanying the painted tiles emerge from Hill’s smoke ghostly and wraithlike, bringing the shadows of past revolts to the present.

Sanctuaries is a series of portrayals of tiled domestic spaces created with ink, graphite, enamel paint and soap. These murky depictions verging on abstraction make visible women’s disparaged and repetitive manual labour in the domestic environment that followed under the conditions of early capitalism. Federici explains that the magical conception of the body and nature, which predominated in the Middle Ages, was at odds with the desire of the capitalist class to transform the labouring human body into a machine. Examined in light of Federici’s argument, Anyango’s depiction of soulless mechanical labour reads as a melancholy and poetic expression of mourning that stems from the loss of magic. The pairing of the loss and societal repudiation of magic with the deviant perseverance of the supernatural is what makes Ladies’ Room a powerful articulation of political conflict and struggle against masculine discipline.

Catherine Clément writes about sorcery and hysteria:

The sorceress heals, against the Church’s canon; she performs abortions, favors nonconjugal love, converts the unlovable space of a stifling Christianity. The hysteric unties family bonds, introduces disorder into the well-regulated unfolding of everyday life, gives rise to magic in ostensible reason.9

She goes on to add, however, that even though the witch and the hysteric might unsettle the phallocentric status quo, these two figures are also forced into a conservative frame of representation. The witch is always destroyed and only mythical traces remain of her existence. The hysteric is relentlessly speculated on by her analyst and concerned family, and she is forever bound to the authoritative rhetoric of ‘cure’ which might ostracise her as incurable and unfit to operate under prevailing societal norms.10

In Hill and Anyango’s Ladies' Room these two figures survive. The words of the unhinged hysteric are heard in the absence of the analyst and without a suggested line of treatment. The healing magic of the witch’s herbalist practices is lauded and, despite the smoke lingering throughout the cloakroom, there is no smell of burning flesh. In Ladies’ Room, magic remains and refuses to be fully extirpated. Imagining the ladies room as a space of resistance and drawing from the figure of the witch may also open further productive avenues for queering expressions of gender and sexuality; ultimately, the witch is an indomitable personification of insubordination11 with the desire and potential to transgress the phallocentric sex/gender binary. The artists went as far as to experiment with alchemy and create their own mysterious red potion, reminiscent of the blood potion in Suspiria and named Vodka Blush in homage to Rosemary’s Baby. The effects of the potion on those who consumed it are yet to be reported.

Silvia Federici writes that practicing magic as a healer, midwife, herbalist or maker of love potions was a source of employment and power for many women in pre-capitalist societies. Untamed female sexuality, which has historically been associated with disorder and disruption of discipline, has always been seen as the core of women’s magic.6 When the foundation of capitalism was laid out during the land enclosures and the introduction of exploitative wage labour, women’s sorcery – which entailed methods of abortion and contraception — became a serious threat to inducing the new social and economic hierarchies and had to be eradicated. Federici argues that the barbaric witch hunts resulted in a new model of femininity better suited to the development of masculine capitalist societies and gendered division of labour: ‘sexless, obedient, submissive, resigned to subordination to the male world, accepting as natural their confinement to a sphere of reproductive activities’.7 The legal prohibition of birth control and abortion under such conditions was an attempt to ensure the steady reproduction of new labour force8 and to bind women to the domestic sphere of unpaid labour as compliant wives and mothers. Silent Companion meditatively reveals the subversive legacies of witchcraft that could protect women from the confines of motherhood and housework, and the consequent economic dependency on men. The dummy boards accompanying the painted tiles emerge from Hill’s smoke ghostly and wraithlike, bringing the shadows of past revolts to the present.

Sanctuaries is a series of portrayals of tiled domestic spaces created with ink, graphite, enamel paint and soap. These murky depictions verging on abstraction make visible women’s disparaged and repetitive manual labour in the domestic environment that followed under the conditions of early capitalism. Federici explains that the magical conception of the body and nature, which predominated in the Middle Ages, was at odds with the desire of the capitalist class to transform the labouring human body into a machine. Examined in light of Federici’s argument, Anyango’s depiction of soulless mechanical labour reads as a melancholy and poetic expression of mourning that stems from the loss of magic. The pairing of the loss and societal repudiation of magic with the deviant perseverance of the supernatural is what makes Ladies’ Room a powerful articulation of political conflict and struggle against masculine discipline.

Catherine Clément writes about sorcery and hysteria:

The sorceress heals, against the Church’s canon; she performs abortions, favors nonconjugal love, converts the unlovable space of a stifling Christianity. The hysteric unties family bonds, introduces disorder into the well-regulated unfolding of everyday life, gives rise to magic in ostensible reason.9

She goes on to add, however, that even though the witch and the hysteric might unsettle the phallocentric status quo, these two figures are also forced into a conservative frame of representation. The witch is always destroyed and only mythical traces remain of her existence. The hysteric is relentlessly speculated on by her analyst and concerned family, and she is forever bound to the authoritative rhetoric of ‘cure’ which might ostracise her as incurable and unfit to operate under prevailing societal norms.10

In Hill and Anyango’s Ladies' Room these two figures survive. The words of the unhinged hysteric are heard in the absence of the analyst and without a suggested line of treatment. The healing magic of the witch’s herbalist practices is lauded and, despite the smoke lingering throughout the cloakroom, there is no smell of burning flesh. In Ladies’ Room, magic remains and refuses to be fully extirpated. Imagining the ladies room as a space of resistance and drawing from the figure of the witch may also open further productive avenues for queering expressions of gender and sexuality; ultimately, the witch is an indomitable personification of insubordination11 with the desire and potential to transgress the phallocentric sex/gender binary. The artists went as far as to experiment with alchemy and create their own mysterious red potion, reminiscent of the blood potion in Suspiria and named Vodka Blush in homage to Rosemary’s Baby. The effects of the potion on those who consumed it are yet to be reported.

NOTES

1 Hélène, 'The Laugh of the Medusa', Signs, vol. 1, no 4, Summer 1976, pp. 875-893 (p. 877)

2 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), p. 5

3 Jacqueline Reich, 'The Mother of All Horror: Witches, Gender, and the Films of Dario Argento' in Monsters in the Italian Literary Imagination, ed. Keala Jewell (Wayne State University Press, 2001), p. 97

4 Jacqueline Reich, 'The Mother of All Horror: Witches, Gender, and the Films of Dario Argento' in Monsters in the Italian Literary Imagination, ed. Keala Jewell (Wayne State University Press, 2001), pp. 92-94

5 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), pp. 5, 8

6 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), pp. 8-9

7 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), p. 13

8 Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (PM Press, 2012), p. 97

9 Catherine Clément, 'The Guilty One' in The Newly Born Woman (University of Minnesota Press, 2008; originally published by Union Générale d'Éditions, Paris in 1975), p. 5

10 Catherine Clément, 'The Guilty One' in The Newly Born Woman (University of Minnesota Press, 2008; originally published by Union Générale d'Éditions, Paris in 1975), p. 5

11 Anna Colin, Witches: Hunted Appropriated Empowered Queered (B42, 2013), p. 107

1 Hélène, 'The Laugh of the Medusa', Signs, vol. 1, no 4, Summer 1976, pp. 875-893 (p. 877)

2 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), p. 5

3 Jacqueline Reich, 'The Mother of All Horror: Witches, Gender, and the Films of Dario Argento' in Monsters in the Italian Literary Imagination, ed. Keala Jewell (Wayne State University Press, 2001), p. 97

4 Jacqueline Reich, 'The Mother of All Horror: Witches, Gender, and the Films of Dario Argento' in Monsters in the Italian Literary Imagination, ed. Keala Jewell (Wayne State University Press, 2001), pp. 92-94

5 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), pp. 5, 8

6 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), pp. 8-9

7 Silvia Federici, 'Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women' in 100 Notes — 100 Thoughts: No 096 (Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2012), p. 13

8 Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle (PM Press, 2012), p. 97

9 Catherine Clément, 'The Guilty One' in The Newly Born Woman (University of Minnesota Press, 2008; originally published by Union Générale d'Éditions, Paris in 1975), p. 5

10 Catherine Clément, 'The Guilty One' in The Newly Born Woman (University of Minnesota Press, 2008; originally published by Union Générale d'Éditions, Paris in 1975), p. 5

11 Anna Colin, Witches: Hunted Appropriated Empowered Queered (B42, 2013), p. 107