Artists Sonia Levy and Karen Kramer submerge Verksmiðjan, in the Icelandic village of Hjalteyri, into the depths of the sea with Hafrún. The first collaborative exhibition between the two London based artists, Hafrún interweaves Levy and Kramer’s sustained enquiry into marine life, anthropogenic environmental change and entanglements between lifeforms and ecosystems through installation and artist moving image. The exhibition is saturated with the history of its architectural context, a former herring factory, which was swiftly constructed with a concrete mix of cement, aggregate and seawater to respond to the needs of the fishing industry in 1950. Since then abandoned by the profit-making agents who commissioned it, the old factory is now a ruin of industrial production, vibrant with the traces of watery histories embedded to its materiality.

Hafrún is the name given posthumously to the oldest known ocean quahog, who was dredged off the coast of Grímsey in 2006 and died soon after in the hands of scientists. At the time of being captured, Hafrún was 507 years old, having lived through all three historical eras that have been proposed to mark the beginning of the Anthropocene1: the Western colonial invasion of the Americas, the Industrial Revolution, and the 20th century Great Acceleration, characterised by the rapid development of nuclear technologies. Like the growth rings of trees, ocean quahogs’ shells carry a detailed record of the conditions in which the clams have lived. The shells are now studied as material archives that capture centuries of environmental change and, with paradigms developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, they are analysed to forecast ecological futures of the planet.

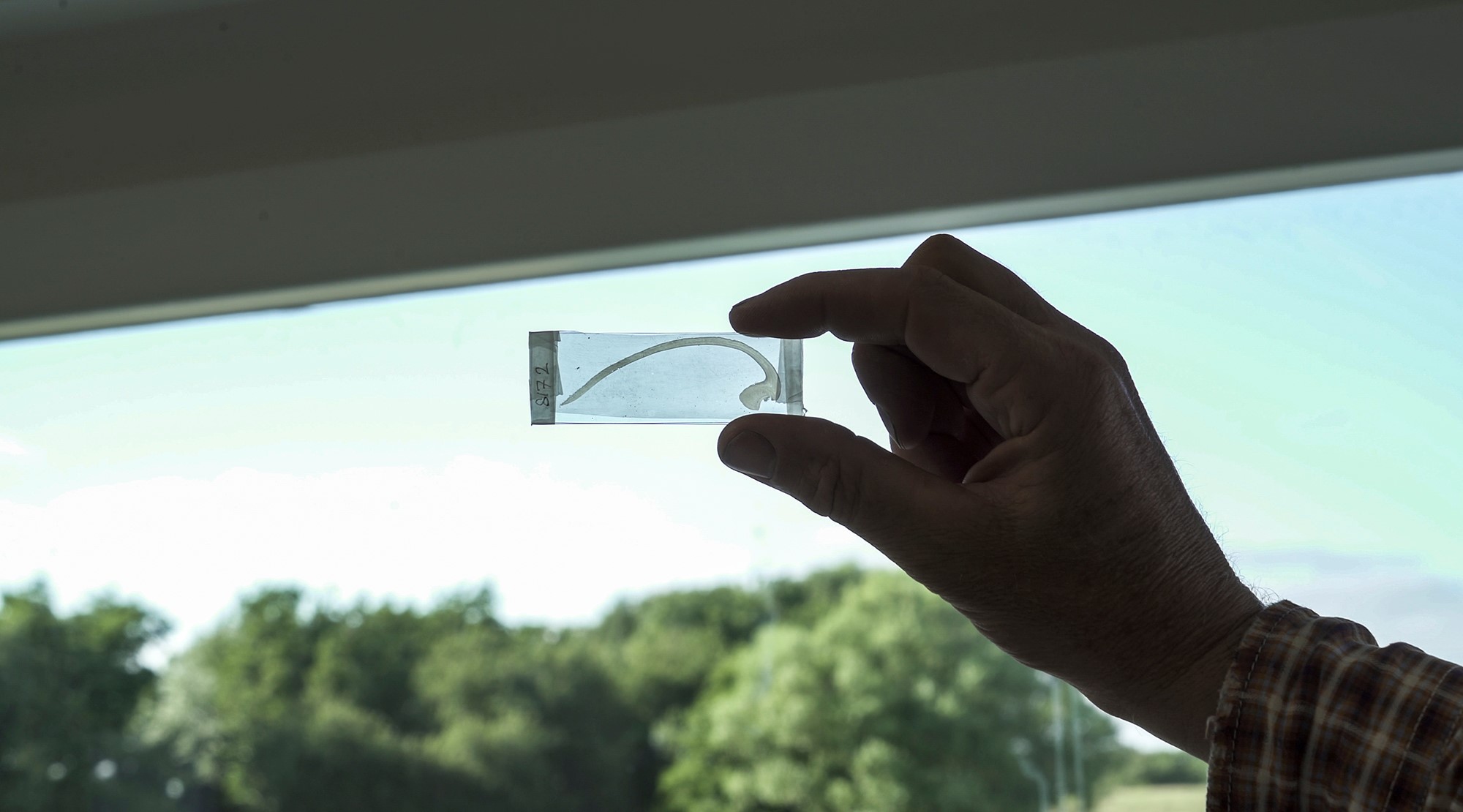

The exhibition is anchored in Levy’s eponymous project (Hafrún, 2019) filmed in collaboration with diver Erlendur Bogasson. The two-channel video installation portrays the laboratory process of collecting data from ocean quahogs’ shells. The shells are meticulously numbered, measured, embedded in resin and cut to study the patterns within their intricate internal layers, which on a microscopic scale evoke topographic maps of ancient landscapes. The rigorous process of extraction and analysis is paired with Bogasson’s underwater footage from a series of hydrothermal vents at an unusually shallow depth near the northern coast of Iceland. It is near these vents where Hafrún was found over a decade ago. These openings on the seafloor, through which geothermally heated water flows into the cold sea, host complex communities of marine organisms and have been theorised as one possible location for the origin of life.

Hafrún’s sex was never determined, but their given name is feminine and denotes a mysterious symbol connected to the sea. Evoking the notion of Woman as the mysterious other and the deep, dark sea as otherworldly and unfathomable in its vastness, the case of Hafrún brings forth the prevailing association between the sea and women’s bodies. Both appear in the Western cultural imaginary as unpredictable, controlled by liquid flows, attuned to the moon and, above all, as generators of life. Within this tangled mystification of oceans and femininity, Levy makes visible the frequent position of the masculine natural scientist as the one who dissects and decodes the mysteries hidden within the depths of amorphous matter. But as feminist scholar Astrida Neimanis writes, watery embodiment is not only specific to women or femininity. Rather, it is something to which we are all equally connected. The main constituent component of our bodies, water flows through all of us without differentiation, sustains us and, through our dependence on it, inherently connects us to other bodies of water.2

Levy’s For the Love of Corals (2018), the predecessor of Hafrún, addresses our indebtedness to, and responsibility towards, our aqueous companions. The project follows a team of marine biologists and aquarists in the basement of the Horniman Museum and Gardens in London, as they work on their pioneering coral reproduction research. By simulating the environmental conditions of the Great Barrier Reef in their ad-hoc laboratory, the team became the first in the world to successfully breed corals in captivity. Levy’s two-channel film examines the potential of the museum to host a collaborative survival endeavour between species, as new paradigms for environmental conservation and natural history emerge in the face of accelerated ecological decline. While the museum context may still echo the Enlightenment values of human mastery over nature — after all, the corals are kept in captivity as part of the Horniman’s ‘living collection’ — the shared attempt to save corals from their anthropogenic extinction also establishes a new generative assemblage of living beings and biotechnology. Levy shows how the scientists and the coral create their own world in common through the daily labour of life-affirming care.

Sonia Levy & Karen Kramer: Hafrún

Sonia Levy, Hafrún (2019), video still

Commissioned for the exhibition

Sonia Levy & Karen Kramer: Hafrún

Verksmiðjan

14 September – 13 October 2019

Sonia Levy & Karen Kramer: Hafrún

Verksmiðjan

14 September – 13 October 2019

Karen Kramer, The eye that articulates belongs on land (2016), video still

Although Levy, too, maintains an ambivalent attitude towards scientific innovation, it is in Kramer’s filmic fables that humans’ technological advances, especially in their collisions with bodies of water, unfold the full extent of their ominous potential. In Limulus (2013), a deflated Mickey Mouse balloon, now worn and forgotten ocean debris, relates its encounter with a horseshoe crab on the ocean floor. Our ghostly narrator has borne witness to the distress of the aquatic being who, after 450 million years on Earth, is now on the brink of extinction because humans have ceaselessly harvested its blood for pharmaceutical consumption. The tale is interjected by a Seeburg Olympian jukebox, a recent yet already redundant technological invention, accentuating the short-lived relevance of human endeavours. With Limulus, Kramer attends to timescales beyond human existence to make palpable the damage that our self-preserving species has caused to prehistoric life forms, next to whom our own appearance on this planet is only a brief sojourn.

Hafrún, For the Love of Corals and Limulus articulate the myriad ways in which humans have studied, intervened with, harvested from and sought to master bodies of water. Diverting from this narrative, Kramer’s The eye that articulates belongs on land (2016) portrays water as a fundamentally uncontrollable force that also holds power over life on terra firma. Scanning the coastal landscapes of eastern Japan affected by the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which led to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the film considers the threshold between land and sea, and the unthinkable temporalities inherent to the aftermath of a nuclear meltdown. The roam across these deserted sites is guided by the narration of Sasaki, a mummified Hokkaido fox. An entity caught between worlds and timelines, Sasaki recalls the catastrophic event and, grief-stricken, reflects on the insignificance of the coastline as the ostensible boundary, which humans had imagined would keep them separate from the sea. Kramer’s contemporary fable is a sombre gaze at the ramifications of hazardous human-made technologies reconfigured by natural forces.

At Verksmiðjan, Levy and Kramer float through and amongst bodies of water with care and caution, mindful of their vulnerability as well as their strength. With Kramer’s installation evoking the undulation of submerged reeds and Levy and Bogasson’s underwater footage, the artists bring to life the watery origins of the building itself. The concrete architecture of the capitalist ruin turns into a reef, where different life forms and ideas can again take hold to imagine futures beyond human existence. Brought together, Levy and Kramer’s work presents a generative expansion of artistic devices, through which it might be possible to address and grasp the intensity of the imminent ecological crises that have already begun to unfold.

Hafrún, For the Love of Corals and Limulus articulate the myriad ways in which humans have studied, intervened with, harvested from and sought to master bodies of water. Diverting from this narrative, Kramer’s The eye that articulates belongs on land (2016) portrays water as a fundamentally uncontrollable force that also holds power over life on terra firma. Scanning the coastal landscapes of eastern Japan affected by the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which led to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the film considers the threshold between land and sea, and the unthinkable temporalities inherent to the aftermath of a nuclear meltdown. The roam across these deserted sites is guided by the narration of Sasaki, a mummified Hokkaido fox. An entity caught between worlds and timelines, Sasaki recalls the catastrophic event and, grief-stricken, reflects on the insignificance of the coastline as the ostensible boundary, which humans had imagined would keep them separate from the sea. Kramer’s contemporary fable is a sombre gaze at the ramifications of hazardous human-made technologies reconfigured by natural forces.

At Verksmiðjan, Levy and Kramer float through and amongst bodies of water with care and caution, mindful of their vulnerability as well as their strength. With Kramer’s installation evoking the undulation of submerged reeds and Levy and Bogasson’s underwater footage, the artists bring to life the watery origins of the building itself. The concrete architecture of the capitalist ruin turns into a reef, where different life forms and ideas can again take hold to imagine futures beyond human existence. Brought together, Levy and Kramer’s work presents a generative expansion of artistic devices, through which it might be possible to address and grasp the intensity of the imminent ecological crises that have already begun to unfold.

NOTES

1 The epoch defined by increased impact of human activity on the Earth’s ecosystems and geology.

2 Astrida Neimanis, 'Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water' in Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice, eds. Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni and Fanny Söderbäck (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 88-91

1 The epoch defined by increased impact of human activity on the Earth’s ecosystems and geology.

2 Astrida Neimanis, 'Hydrofeminism: Or, On Becoming a Body of Water' in Undutiful Daughters: Mobilizing Future Concepts, Bodies and Subjectivities in Feminist Thought and Practice, eds. Henriette Gunkel, Chrysanthi Nigianni and Fanny Söderbäck (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), pp. 88-91